I lost the battle but not the war

On the 30th August, 2018, I set-off from the port of Eden in South-East Australia, in a solo attempt to row across the Tasman Sea to New Zealand and finish the Rowing from Home to Home expedition. Rowing from Home to Home is a journey I am attempting to make from Singapore to New Zealand completely by human power.

This was my second attempt at finishing the expedition, after a 24-day effort in October and November 2017 saw me turn back whilst 400km off the coast of mainland Australia due to adverse winds. Not once during those frustrating 24 days did I have favourable wind conditions to move me towards New Zealand and the success of any ocean rowing endeavour is at the mercy of the wind. During that 24 day period I had rowed a total distance of 1,100nm (over 2,000km) which is equivalent to the total length of a Tasman crossing but I had made a very large circuit which ended back in Australia in the small fishing port of Ballina – further away from New Zealand than where I had started from (Coffs Harbour).

I then decided to re-strategise my departure point, route and timing of departure for a second attempt. I cycled for 13 days from Ballina, 1,300km down the east coast of Australia, through Sydney and over the iconic harbour bridge, all the way to the town of Eden in the south of Australia. Eden is a small fishing port located close to the border between Victoria and New South Wales.

Why head south?

The reason for moving south was to get closer to the 40 degree latitude line or the roaring forties. There are basically two choices when rowing across the Tasman from Australia to New Zealand. The mid-Tasman route or the Southern Tasman route.

There is considerable difference between the two routes. The mid-Tasman route departs from somewhere between Sydney and Coff’s Harbour, whilst the southern Tasman route is much lower, and departs from Tasmania or Eden. The water and air temperature is much colder on the southern route (water is around 12 – 13 degrees down south as opposed to 21 degrees higher up), the likelihood of gales is much higher and the sea-state is rougher. But, the wind has more of a westerly component in the south and it is a slightly shorter crossing to New Zealand. The weather systems down south come through much faster than they do in the mid-Tasman so even the gales generally don’t last more than 24 hours. Currents tends to be more of an issue on the mid-Tasman route, with more eddies to negotiate than further south. I planned to take advantage of the westerly winds in the southern Tasman route for my second attempt. Currently no one has successfully crossed the southern Tasman route all the way from Australia to New Zealand.

Round Two

I did not want the added pressure of media covering my departure with reporters hounding me for departure dates and times on a daily basis so I deliberately kept my details low-key and did not post updates on my website about my intentions.

The local wharf in Eden had kindly allowed me to tie up for free however their rules required me to sleep on the boat. After eleven days and nights bumping away tied alongside (the jetty is not sheltered from southerly winds which often blow through), I set off on the 30 August, 2018. Strong westerly winds were forecast on the evening of day two which I intended to make full use of to help move me towards New Zealand.

Day one started well, I rowed for nine hours straight to get away from land on a beautiful day with a light northerly breeze. I was accompanied by pods of dolphins and two large whales. By darkness that evening I was 20nm from Eden and 7nm offshore, having made use of a southerly setting current to move generally south-east. I knew I would be passing through the busy shipping lanes later that evening which are 10nm – 20nm offshore. This was a night with no sleep, and saw me on the radio, communicating with vessels throughout the night to ensure we kept safe passing distances. My experience in the first attempt in the shipping lanes for 6 days and nights was very useful. The wind was starting to increase now and with occasional rain and poor visibility, the SIMRAD AIS (Automatic Identification System) and VHF radio worked beautifully and was critical to our safety through the night. Five massive vessels at over 200m in length and travelling at 15 knots passed within 1nm of Simpson’s Donkey with the closest steel giant only 800m off our stern. The crew of these vessels without exception, proved professional, vigilant and the cooperation was straight forward as we chatted over the radio to ensure everyone was safely passing.

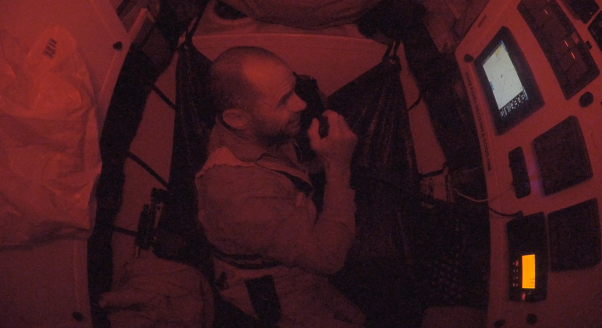

On the radio in the cabin during the 1st night.

By the morning of day two we were out of the shipping lanes and still moving south-east at around two knots. The wind picked up all day as we bumped along, and I was aiming to get to 38 degrees south before turning east to New Zealand. Gale force winds were forecast to hit around 9PM that evening. I was both excited and apprehensive about the wind. Excited that it would be the first time in 26 days rowing on the Tasman that I finally had some decent wind blowing me towards New Zealand (‘free miles’ in ocean rowing terms), and apprehensive at how best to set the boat up to maximise and safely handle these conditions while still making miles. Even though the wind was going to be strong I was determined to utilise it to make as much ground as possible.

I readied the boat in the twilight. and secured and strapped the deck down. At 9PM in the darkness, I engaged the small SIMRAD electric autopilot, set it on a heading due east and climbed into my sleeping bag in the cabin. As the wind picked up into the late evening and early hours of the morning, things worked to plan. We were being pushed along towards New Zealand with the autopilot keeping the boat straight and on a constant easterly heading.

The sea-state grew during the night as the wind increased, and as it did the waves started to become more confused in their directions, with some starting to break. I was now close to the region just to the east of Bass Strait, a notoriously ‘bumpy’ part of the world. We were making great progress towards New Zealand, however at 4AM we were flipped over (rolled or capsized) by a breaking wave that came in from our port quarter. Now Simpson’s Donkey is designed to roll over and automatically self-right and indeed she functioned as designed, rolling back over in a few seconds and shaking the water off. I was thrown about in the cabin and enough water got in through the partially open air vent to wet my sleeping bag. I began adjusting the course on the autopilot to try to find the best heading to keep us from rolling again yet still make miles to New Zealand. However 1.5 hours later we got caught by another wave and were flipped again. We again rolled back up quickly, but I decided it was time to make come changes.

Crawling out onto the back deck in the dim light of the early morning, I began to manually steer. This is where I sit on the deck with the steering lines in my hand facing the stern of the boat and the oncoming waves. This worked well, and I was able to quickly kick the heading of the boat around to ensure we were always lined up with the breaking waves. We were hitting 15 knots of speed as we surfed the breaking waves and it really was tremendously exhilarating and a lot of fun. Unfortunately the power of the waves hitting the back deck snapped in half two of my spare carbon fibre oars, which gives an indication of the force of the water.

However sitting in the back deck was cold. Even though I was in my goretex drysuit with thermal sharkskin under-layers, without the effect of rowing to warm my body and with the water up to my chest at times when then the waves broke over the boat I was soon getting uncomfortably cold and knew this was not a long-term option. So I deployed my drogue (very small parachute, only 1 – 2 feet in diameter) off the stern to slow us down and stabilise the boat somewhat. All morning the sea state picked up and the sea really was very messy and we eventually rolled a third time. This time the boat took a little longer to self-right, around a minute or two before we slowly came back over. I believe the righting was affected by the drogue attached to the stern and/or due to the fact there was a little more water in the cabin that had snuck in through the vents. It was definitely a most interesting experience to be inside the cabin with the boat upside down, standing on the roof and looking out the back hatch when we were completely underwater – in effect the view out a submarine port hole. After some rocking back and forth while inside the cabin, combined with some favorable wave action she came back up again, the boat no worse for wear, but the rower now ready for a change of underpants!

I finally decided I had been stubborn enough and it was time to sacrifice progress for stability and deployed the parachute anchor. The parachute anchor is a large 9-foot diameter underwater parachute which I deploy off a long line attached to a U-bolt mounted on the bow. The parachute holds the bow of the boat into the direction of the wind, which generally (although not always, especially on this route) is the direction from which the waves are coming from, and in effect allows us to ride out rough weather in the safest way possible.

Life in the dry suit in the cabin

After a few hours bouncing away on para-anchor, with no more rolls and the situation under control, it was just a matter of waiting out the storm till the next morning before getting under way again. Unfortunately, in the early hours of the afternoon I heard a noise and felt the motion of the boat change. I knew instantly we were not on para anchor anymore. Clambering onto the back deck my suspicions were confirmed as I saw the para anchor was now held to the boat only by the small retrieval line (it should have been anchored to a solid U-bolt on the bow by the main deployment line). At this stage I was not sure why it was no longer attached to the bow however further investigation would require taking a swim and in these conditions that was out of the question (5m breaking waves from different directions and 35+knots of wind). So I pulled in a enough of the para anchor line to deploy it from the stern. This is not an ideal method to deploy the para anchor from on this boat, but it got us through the following night.

An 18 dollar bolt

By the morning of day four, the wind was back down to a manageable 20 – 25 knots, the sea had calmed down slightly and life was looking rosier. However upon pulling in the para anchor, I found fastened to the end of the rope the U-bolt that was meant to be solidly screwed into the bow.

This was a very bad situation, the U-bolt is the single point on the bow where I secure the parachute anchor. It is a critical piece of equipment and is made from stainless steel with a 4000kg breaking strain. It had snapped completely off. There is no back-up bolt. At that very moment, life completely changed.

The bolt in question in my hand, it snapped at the threads between my fingers.

Decision to abort

As I stood on the back deck and thought about the situation, it took me less than five minutes to come to the conclusion that I would not be continuing the row to New Zealand without a reliable way to para anchor. My options to para anchor now were reduced to rigging some form of bridal off some cleats on the side of the boat, or to deploy it from the stern. Neither of these options were safe long-term solutions (I had already ripped one of the side cleats completely out on the first attempt with the para anchor). Having just spent sometime underwater in an upside down boat, I also was concerned how it would affect the critical self righting of the boat if we flipped with the bridle system in place. On this particular route, not having a reliable way to para anchor so early on in the trip had now propelled me to a level of risk which I was not willing to accept.

After discussions with project manager Dave Field, the call was made to abort the attempt and the decision now was whether I could make it back to Australia in time before the next gale hit under my own power. ‘Clouds’ – the expedition meteorologist predicted I would get close and that we had three days of good weather coming up, before the next northerly system would hit. But I would not get all the way in before needing to weather another potential northerly gale. With a well-functioning parachute anchor this would not be an issue, but without it, I was not prepared to accept this level of risk either.

So the decision was made to use the three-day fair weather window to arrange a controlled and safe pick-up by a passing ship. After some phone calls with the Australian Maritime Search and Rescue who coordinate these pick-ups, they confirmed a vessel would be passing by within 12 hours. As I was in no immediate danger this was good news for me, however when the Search and Rescue machine kicks into action it is truly impressive and has a mind of its own. They asked me to standby for an hour whilst they made a plan before informing me they had made the decision to send a rescue helicopter instead of waiting for the vessel, which would arrive in around 2.5 hours time. With the excellent communications systems we had onboard (multiple tracking systems, sat phones, VHF radio and multiple epirb and plb beacons), the process went very smoothly and after lunch on day four I was picked up by a very competent and professional helicopter crew and flown back to the mainland. As we flew off, I said goodbye to the little Donkey, a boat I had now travelled and lived in for over 6,500km in the last two years.

The last photo of Simpson’s Donkey as taken from the rescue helicopter. Photo: Bryce England

The end of the expedition

Within 5 hours of landing in Australia I was on the plane back to Singapore. My worldly possessions were my passport and credit card and some borrowed clothes the helicopter crew had kindly loaned me (plus a very wet drysuit). I could not sleep on the overnight flight back to Singapore. By this stage I had hardly slept for four nights and days but my mind raced as I went through the events that had unfolded the last four days, over and over again. What could I have done differently? Had I made the right decisions along the way? What did the future entail now? I did not at this stage know the answer to any of these.

What I did know was that the expedition was now dead. I had lost my beloved donkey. There was no way I had the resources or the energy to get another boat and attempt this again. I had no insurance for the boat as I could find no one too insure her. Seven years of my life and so much effort and support from others had been invested in this project. Everything was a blur by the time I landed in Singapore in the early hours of the morning. Stephanie picked me up from the airport and I gabbled a stream of random, depressed and tired thoughts as we drove home. Once home, I quietly snuck into my daughter’s room and lay down on the mattress beside them. Rachel felt my presence and rolled over in the darkness, reaching her little hand out until it touched my hairy face. Feeling the whiskers it took her a few seconds to process who it was. “Dada!” she cried out in the darkness. Finally I could sleep.

The Donkey comes home

When I woke up later that afternoon with my thoughts clearer, I immediately began checking the position of Simpson’s Donkey. I had left the AIS running, so could track her exact location. Over the course of the next three days, with coordination and the expertise of weather guru Roger ‘Clouds’ Badham’s predictions of wind and current together with the Eden Marine Police, we saw she would be around 50 – 60km off the coast and there was small window of opportunity to tow her into shore before the strong winds hit. I have much gratitude for the people involved from the Australian Maritime Search and Rescue, to the helicopter crew – Pilot Bryce England, Air Crewman Darren Magor, Dr Gerrard Marmor and paramedic and swimmer Justin Hockley, absolute legends, your professionalism, empathy and support for what I am trying to do is hugely appreciated. Also the marine police in Eden and the Eden Marine rescue who all played their roles in coordinating my pick-up and the subsequent tow-in of Simpson’s Donkey. You are a credit to your service and what an asset to the Australian people and visitors to your shores.

The boys from the TOLL rescue chopper coming into the rescue

The people of Eden whom I have dealt have also been wonderfully supportive and I cannot thank them enough for their generosity of spirit. Eden is a fishing port with a long and proud seafaring history. It has been touching to see how people whose lives are formed and shaped around the sea, support fellow seafarers in their times of need. I will indeed pay their support forward.

(A special thank you to Robyn Malcolm, David Richardson and the Lucas family who could rescue a downed airliner in 4000m of water if they put their collective skills and minds to it.)

What now?

I have two options open to me. I could give up, put it into the ‘too hard bin’, move on with life and wake up every day for the rest of my life with regret. Or I can use what I have learnt and the experience gained to make another attempt. No one has successfully crossed this route – there is no manual to follow. At the end of the day I prepare the best I can and then there is nothing left but to get out there and have a crack.

We are all only as strong as our weakest links. In this case an $18 bolt was the weak link in the chain. The same bolt which has been used and never yet failed on 60 other vessels which have successfully rowed across crossed the Pacific, the Indian and the Atlantic Oceans. But the Southern Tasman route does not seem to care about other oceans – she makes her own rules. Any weakness she pounces upon, rips wide open and lays bare.

Simpson’s Donkey is being modified and strengthened in key areas and being prepared for another attempt at the Tasman in the not too distant future. I have never once lost the belief that I can cross the Tasman solo, safely and in record time. I also never chose this journey because I thought it would be easy, rather the opposite. To find such a challenge to finish off such an expedition somehow seems very fitting. It is a privilege to find something that tests me, pushes me to my limits and motivates me at the same time. I am very aware of the risks and the limits of how much I am prepared to accept. I will continue to make decisions which reflect this and as with the previous two attempts I would rather pull out before the situations get critical and live to fight another day.

I have also learnt through this last attempt that I missed the blogging, writing and sharing of the journey a great deal. Writing this post has been a useful and cathartic process in helping me arrange my thoughts. I will resume my blogging and sharing the journey for attempt # 3 over the next few months.

Bye for now and thanks for reading.

Captain Axe

Posted on September 23, 2018, in Rowing Home. Bookmark the permalink. 31 Comments.

Well, that came as a real shock, Grant! We’d been keeping an eye on the blog for when you were next going to attempt the crossing, and there you were bumping around in the ocean all that time. Your blog was absolutely captivating, and I found myself with heart in mouth as I read – especially sad to hear of the loss of The Donkey, and then the relief of reading that you’d retrieved her. Thank goodness you’re safe and able to regroup for another attempt. You will make it, and we’re still looking forward to waving you in to New Plymouth. Take care, recover fully, enjoy the family, gather strength, and you’ll be off again.👍🏼

LikeLike

Thanks Diane, see you in NP soon!

LikeLike

Axe, I read your blog through teary eyes, frost-nipped toes, running nose, aching glutes, sore knees and an aching heart (for you) having just summited Mt Kezbec (5033m) in the Georgian Caucasus. Dude, you are a true legend in my books. An inspiration to everyone who has crossed your path. You write descriptively and honestly. Your massive disappointment, not of failure but the frustration of such such a small piece of critical equipment. You challenged a notoriously difficult sea and survived for another day. We both know when it’s time to turn around on a mountain or a sea and not to give up a quest. Many would say it’s madness. Many don’t know they are alive until they undertake a journey that takes them to the edge.

Look back and learn – but tread forward with fierce and unbridled determination my good friend -xR

LikeLike

Hello my old mate. I am only following in your footsteps my friend 🙂 Massive congratulations Mt Kezbec – see you soon somewhere?

LikeLike

The main thing is that you ( and even the Donkey ) are still alive and in one piece!

LikeLike

Yes thats right. And ready for another attempt soon!

LikeLike

Your decision-making was wise. Follow that dream Axe. It will happen 💪 😉

Sent from my HTC

LikeLike

Thanks Judy.

LikeLike

You gave it another go, brush off your own thoughts of failures and bury them. As NOBODY considers you this at all. You have done amazingly well to get this far and with continued and focused attempts and enormous passion and effort.

We look forward to staying tuned in and have no doubt at all you will succeed!

Good luck and lots of luck and support on the next round. Rest up and enjoy.

Regards

Amanda

LikeLike

Thanks Amanda – third time lucky I hope!

LikeLike

Wow Grant. Truely an adventure. So glad you’re safe and The Donkey is too.

LikeLike

Thanks Fiona!

LikeLike

Hi Grant, I sure am glad you are safe, you really do put your neck on the block! Winston Churchill said âNever Give Upâ, the old cliche is 3rd time lucky, I know you think like me, âwhat if I never tried?â Iâm at Ruapehu right now, looking for a weather window for some ski-ing. leaving on 19 October for Nepal, 33 days trekking to Kanchenjunga with a group from ATC, Jamie organising again, we have 7 people going. After our trip to Dolpo in 2016 some of the crew asked when are we going again, so eastern Nepal here we come! Attached a photo of yours truly on Aconcagua. Regards kiwi Jim.

LikeLike

Jimbo! Well done on summit of Aconcagua my friend. Enjoy the skiiing, reminds me of our three peaks in two days saga and then you taking me skiiing on legs that were too tired to snow plough!

LikeLike

So sorry Grant.But you’ll get there in the end. I know you will.

LikeLike

thanks for the belief my friend.

LikeLike

A wonderful account of your last attempt to “Row Home”. Since I first met up with you during your attempts to climb Everest I never had any doubts that whatever the challenge you would complete it successfully. You are certainly an inspirational bloke to follow. You took me up Everest in mind if not in body and I really appreciated that. I like your modesty and your gratitude to the guys who have helped you along the way. Just wanted to tell you that I am still there in the background and wanted to wish you well from across the pond. Cheers and good luck Kate

LikeLike

Lovely to hear from you Kate! Thanks for the well wishes.

LikeLike

Axe mate what a great story you tell I loved it. Great to hear you are safe & sound at home now & wish you & family all the best on the next attempt.regards Kiwi Ken

LikeLike

Thanks Captain Ken!

LikeLike

Axe – an amazing account of an incredible journey. So pleased to have you safely back on terre fermer.

LikeLike

Thanks Chris.

LikeLike

What a tale Capt Axe!!! Thank you for sharing your adventures with us – I get chills reading it! Needless to say, we are greatly relieved to hear that you and the donkey made it back safe and in one piece.

Hope you get plenty of rest and time with your family!

LikeLike

Thanks Azi, stay warm and safe in Vancouver ok 🙂 I still have your lovely hat!

LikeLike

What a vivid recount of your second attempt. This is awesome mate. Your power of conviction is infectious – continue to strategies as only you know how andctye tyecdestination will be in your grasp. Congratulations to date.. looking forward to reading more

LikeLike

Thanks John – hopefully better news coming next time around!

LikeLike

Axe! If I could Articulate what Di and Ray wrote any better, I would try but simply cannot. “What they said!” I immediately said “matt! he tried again! The lowly picture, soul crushing! So Glad he isn’t lost forever, so Glad neither are you! Living vicariously and as captivated as ever, lyndy x

LikeLike

Lyndy the legend! Nice to hear from you and thanks for the message.

LikeLike

Well done for keeping at it mate. Your dedication and drive are inspiring. You’ll get there and when you do it’s going to be the best feeling in the world. Keep at it!

LikeLike

Grant, bad luck with the failure of such a small and important item. With your guts and determination I am sure you will be back for another attempt.

LikeLike

Thanks Russell – hope things are well with you my Friend!

LikeLike